Interview: Margaret Luthar (Mastering Engineer)

By Simon Daley

If there’s one buzzword in music production and manufacturing that gets thrown around liberally for the purposes of marketing and advertising, it’s “Mastering”.

Whether for Apple’s once omni-present “Mastered for iTunes” (now “Apple Digital Masters”) format or the more substantial “Mastered For Vinyl” program, the word has become a selling tool without much information available to the regular consumer as to what it really means.

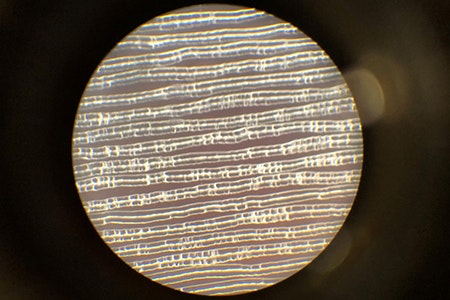

Mastering takes place in a dedicated audio production studio and is the last step before music is distributed digitally or transferred to a physical medium in preparation for vinyl pressing. The second stage of mastering when vinyl production is involved, consists of cutting the mastered audio into either a lacquer disc or DMM copper plate in preparation for the electroplating process.

We recently spoke to Margaret Luthar, an engineer at Welcome to 1979 in Nashville, about how she got into the mastering world, some of her favorite recent projects and what common mistakes she experiences from people submitting mixes for the first time.

Before we dive into your career and recent work, how would you describe the role of a mastering engineer?

We are quality control engineers, bridging the gap between the artistic and manufacturing world. The last step in the artistic process and the first in manufacturing. Unlike the mastering engineers of yore, we are preparing files not just for vinyl release, but for streaming services, CD manufacturing and cassettes. While there is a good amount of creativity, there is also a lot of process-oriented, detailed tasks that are more technical than artistic. Even if you’re not cutting lacquers, you’re going to be sending files off to someone for cutting – so, mastering engineers also need to know the more technical specifications of lacquer cutting that are associated with the quirks of the medium.

How did you first get your start in the music industry and was mastering always the area that you naturally gravitated to?

I was active in band, choir and theater all throughout my childhood so I was always around music. In college, I was a student in the music industry department at Syracuse University. It was a music conservatory-style curriculum but we also took business, law, and marketing courses relevant to the music industry. I was also really interested in political science and international relations, looking back I should have studied electrical engineering AND music. But anyway, our junior year we took a recording class and I realized I was actually really good at this stuff. Or at least, I wanted to get better! After undergrad I went to NYU for my master’s where I honed my skills academically. Then was a string of music festival/institution jobs (Aspen, Banff) and I moved abroad to Norway in 2010 to study for a year at the University of Stavanger, where I started interning at a mastering studio in town. I moved back in 2011 and ended up staying there for 5 years. I did mastering work as well as recording (predominantly acoustic/classical music) and location sound. When I decided to return to the USA in 2016, I wanted to focus on building my mastering career. It fits my personality in a lot of ways. I’m very creative, but I like predictability and repeatable processes. Consistency is important to me, so I think I naturally fit well in the mastering world.

Mastering often seems like a highly specialized field and people may not know how to pursue a career in it. How would you advise someone wanting to get into a mastering role today?

Most people I know have gotten into mastering through recording and mixing. That being said, I know people who have come into the mastering world from being a cutting engineer first, then gradually moving into digital mastering, etc. There’s always more than one way to do something. The similarity is that all of us mastering engineers HAVE to be good at critical listening in a very “objective” way, with the ability to put a client at ease when trusting us with their mixes. Unlike the recording or mix engineer who they might have been working with for months, we are a “new” set of ears and opinions and need to be able to communicate effectively with the artist very quickly. I think if you enjoy a very process-oriented way of working, have a good ear and are able to intuitively “figure clients out” you’re in good shape. I have always been very transparent and honest with people about my life and my workflow. I think honesty in life helps with being a good engineer.

From reading your discography, your work covers many different genres. Do you approach the mastering of a Heavy Rock record in the same way as a contemporary Classical album?

Honestly, yes! I use different gear depending on the projects, but my initial thoughts are always the same. What is this project destined for, vinyl, CD, etc.? Does the artist/client like their mixes or are there issues that need to be addressed? Do I have any concerns when first listening to the music? Any questions? Did they give me all the metadata I asked for or need? I listen to music the same way no matter the genre. There are certain things that are more apparent genre to genre. A metal album has different needs than a classical record. But the start of the process is always the same. I like mastering because I get to listen to all sorts of different music. Punk, rock, funk, jazz, etc. It’s great!

Your social media handle is @livesfordynamics. From your experience would you say the much-debated loudness wars are firmly behind us?

Yes and no. I do think that it is easier for me to make a case for not crushing something to death because we have actual facts that tell us Spotify’s loudness standard is -14 LUFS, for example. I think it presents a good case and makes things easier to understand from a client perspective. I have had an interesting request from a few clients to make sure to not leave any “dead wax” on a record from a visual standpoint, as it seems to the customer like there is “less music.” If your record is plenty loud and I don’t have to use the last .5 inch of disk space, then I would prefer to not use it! There is a visual element to records that is more apparent than say, a CD – so while it was a request I didn’t think I’d hear and cutting a side is definitely more nuanced than dead wax vs used – I can certainly understand the concept.

What have been some of your favorite projects to work on in the last two years?

I’ve worked on a lot of really great music in the last few years. When I was in Chicago (at Chicago Mastering Service), it was always a pleasure to get tapes from Steve Albini because his mixes were so consistent. I also did a lot of work for FPE Records, its founder Matt always put out interesting material. The Avery R. Young record from the label was a highlight of my time in Chicago. So were the Soccer Mommy and Self Defense Family albums. I also got to do a lot of ‘flat cuts’ – audio mastered elsewhere that cut to lacquers. Those were fun projects, including You Won’t Get What You Want by Daughters, Brought To Rot by Laura Jane Grace and an assortment of albums for Merge Records and Fat Possum. While I’m still pretty new here at Welcome To 1979, I’ve also gotten to cut a lot of records for Kindercore, Gold Rush Vinyl and Hand Drawn Records.

Before you go – we’re often asked about the best way to prepare audio files for mastering. What mixing mistakes do you encounter the most in your day to day work, and what advice would you give?

If you were mixing with a limiter, please take it off for mastering. Feel free to send me a bounce of a “rough master” and let me know what you hope to achieve loudness wise, but for the actual file you send to me, please take the limiter off! It helps me with headroom and being able to get things sounding the best they can. Be careful of phase issues from recording and how they translate when you bounce your mix – and, if you’re using effects like phasers or delays it’ll just make all that worse. That’s something that is pretty much impossible to correct in the mastering stage. Too much low end, sure, I can take it out… but phase issues aren’t that simple! If you’re using tape, make sure you’re mindful of why you’re using it. Tape, in all its beauty, can cause a lot of problems if the machine isn’t calibrated correctly or you crush the audio going onto it.

Vinyl specific advice – be mindful of the side length from the get-go. If you give me a 26 minute side for a 12” at 33rpm, I may have to cut it quieter than normal to make it fit on the disc. Not to mention inner groove distortion. If you’re sending me digital files for me to cut from (ie. I’m not doing the digital mastering!), please send me a sheet with start and end times for each track, with each side one long sequence. If you have a lot of frequency content above 20kHz, please take it out! I’m going to remove it anyway as it can cause serious issues for our cutting stylus. Mono-ing the low-end can be helpful, but just being mindful of how much low end is present and how much stereo information it is affecting is also important. Try to curb stereo low end information.

Lastly, don’t be afraid to ask questions. Making records is weird and complicated. Talk to your mastering engineer and the plant you plan to press with. They’ll help you figure things out.

For more information about Margaret’s work, visit livesfordynamics.com.